"When God Created the Intellect": An Analysis of a Weak Hadith

J Little

DPhil Candidate in Oriental Studies

University of Oxford

A friend recently asked me to look into the famous hadith about God’s creation of the Intellect (al-ʿaql). There are many different versions of this hadith, but most share the following wording:

"When God created the Intellect (al-ʿaql), he said to it: “Come forward (aqbil),” and it approached (fa-aqbala); then he said to it, “Go back (adbir),” and it retreated (fa-adbara). Then he said: “I did not create anything better (khayr/aḥsan/aḥabb/aʿjab) than you. Through you I take (bi-ka ākhudhu), and through you I give (wa-bi-ka uʿṭī)."

At first glance, this hadith appears to be supported by an impressive forest of isnads, variously reaching back to Followers, Companions, and especially the Prophet. In such a situation, how could there be any doubt regarding the hadith’s authenticity as a dictum from the earliest Muslims?

In fact, most classical Sunnī Hadith scholars rejected it as weak or fabricated; a leading classical Shīʿī Hadith scholar accepted one version as authentic, but rejected another as weak; and a modern secular study thereon has yielded mixed but largely negative results. What follows is a summary of these versions, judgements, and scholarship, accompanied by some of my own observations.

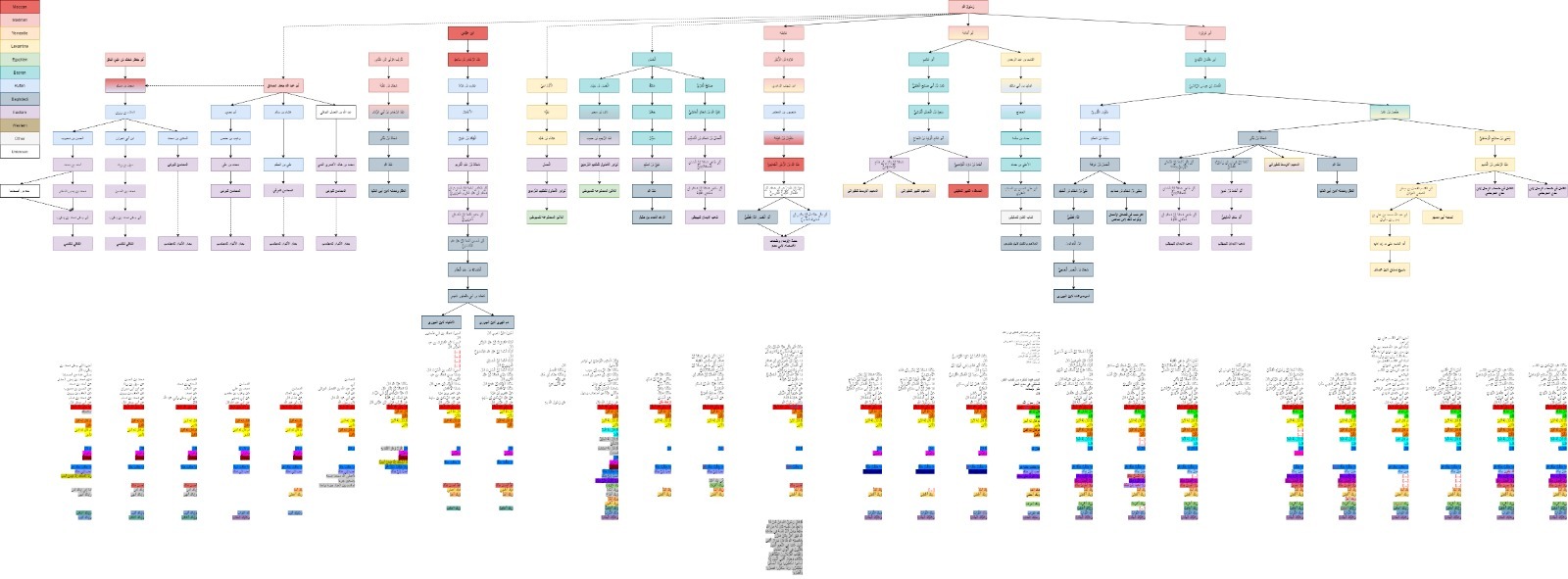

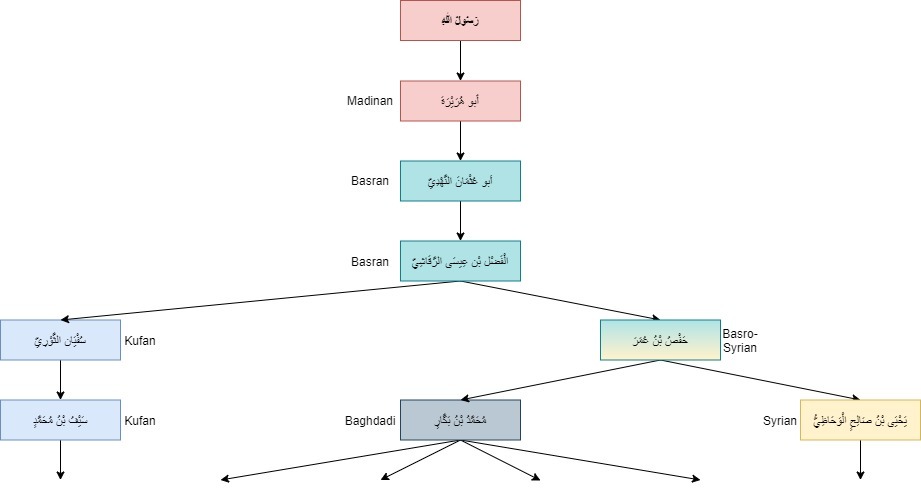

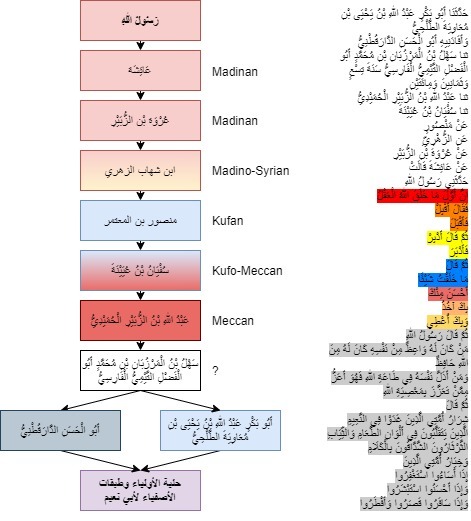

Part 1: The tradition of al-Faḍl

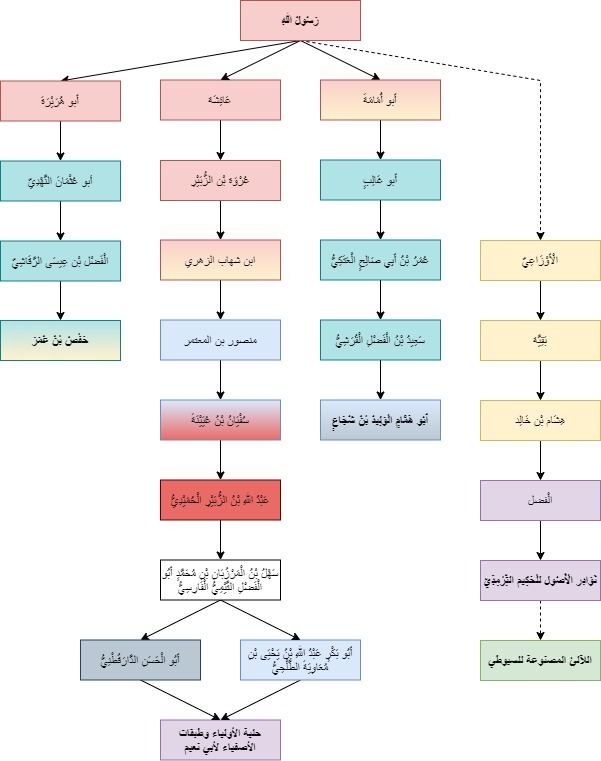

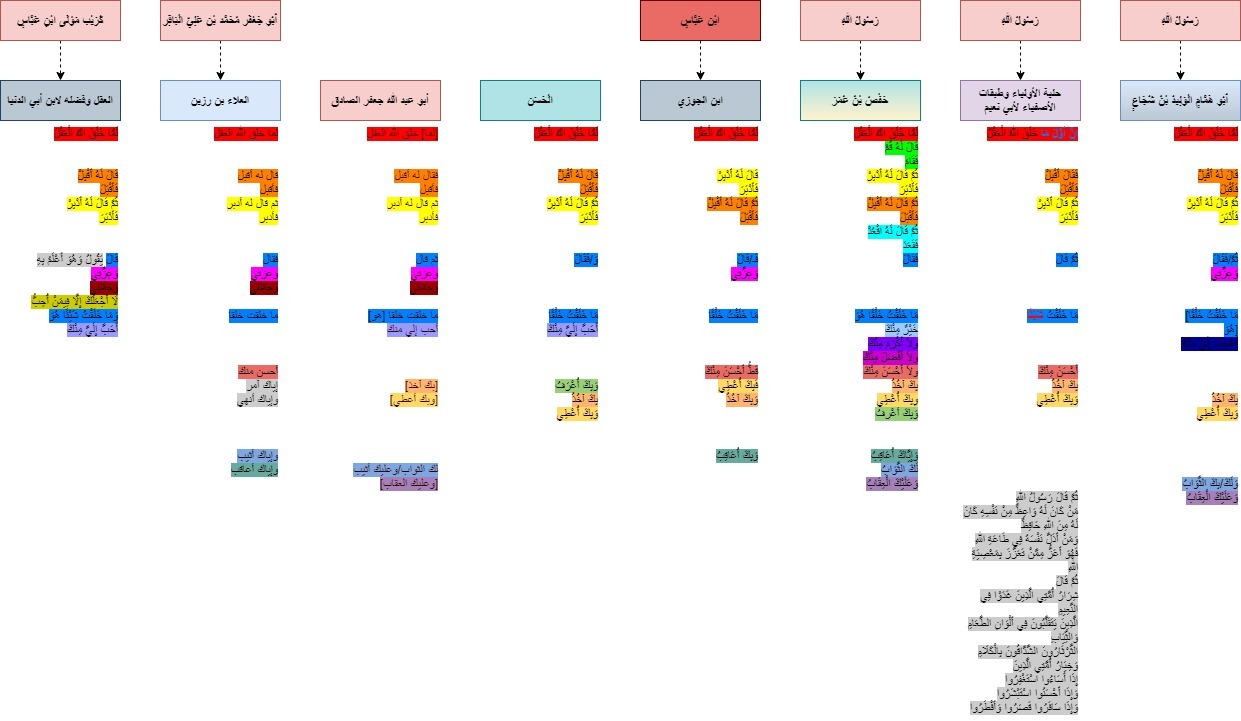

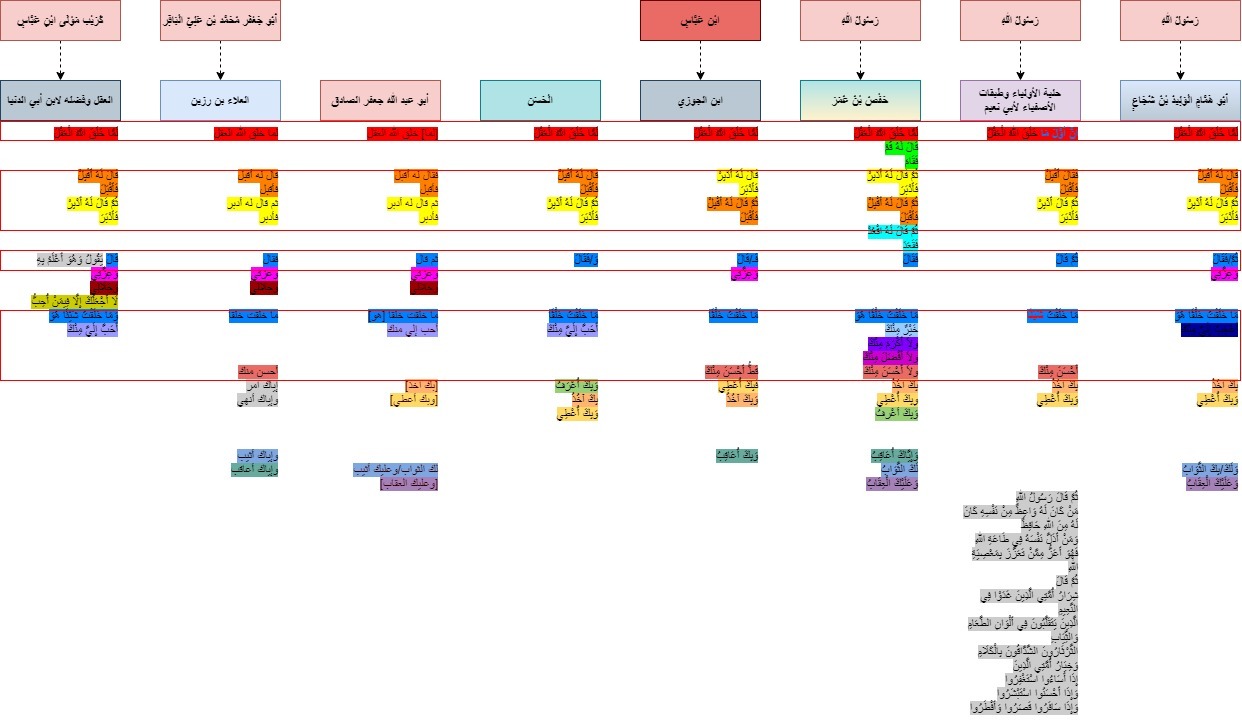

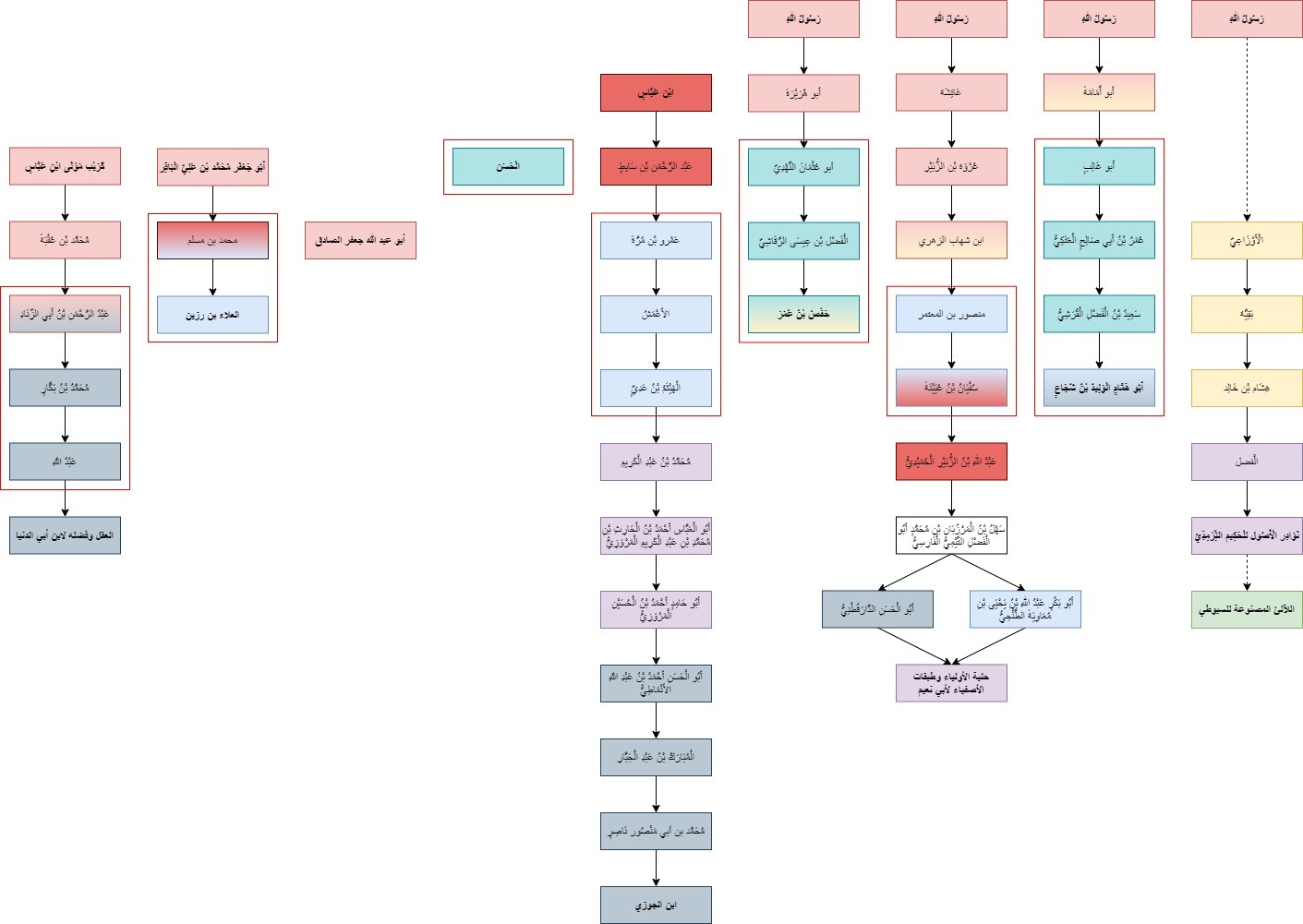

The most common version of this hadith is the family of versions all claiming to derive from al-Faḍl b. ʿĪsā (Basran, Qadarī, d. c. 132/750), from Abū ʿUthmān (Basran, d. 100/718-719), from Abū Hurayrah (Madinan, d. 57-59/676-679), from the Prophet.

According to the isnads, al-Faḍl transmitted this hadith to a Kufan (Sufyān al-Thawrī, who transmitted it to his Kufan nephew Sayf) and a Basran (Ḥafṣ b. ʿUmar), whence it spread to Baghdad and Syria—in the latter case, via the Yaḥyā b. Ṣāliḥ al-Wuḥāẓī (Jahmī, d. 222/836-837), who “belonged to a group of Syrian jurist-traditionists who promoted irjāʾ, and opposed Qadarī notions.”

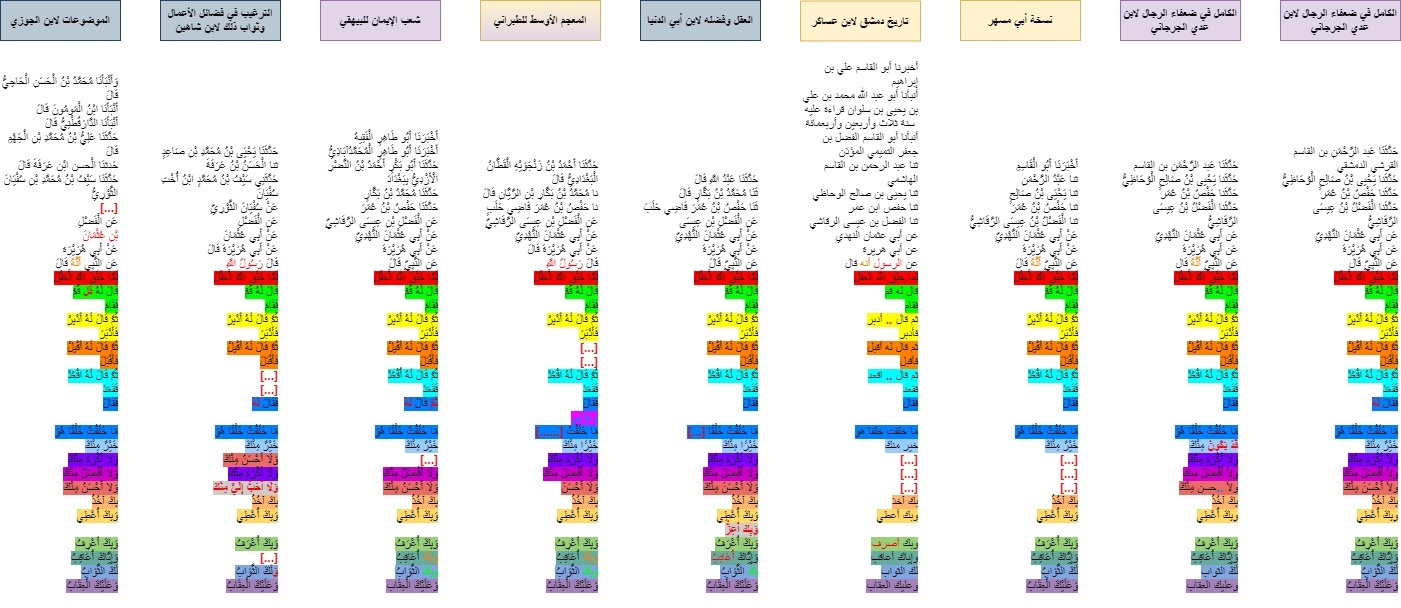

There are quite a few additions, omissions, and alterations across the different extant versions, but these are mostly minor: their matns are mostly similar, and indeed, largely more similar to each other than to other versions.

They thus comprise a distinctive sub-tradition, which is consistent with their reflecting the underlying redaction of al-Faḍl. Thus, on an isnād-cum-matn analysis (ICMA), the following can be reasonably attributed to al-Faḍl, making him a genuine “common link” (CL):

al-Faḍl b. ʿĪsā (Basran, d. c. 132/750): "…from Abū ʿUthmān al-Nahdī, from Abū Hurayrah, from the Prophet, that he said: “When God created the Intellect, he said to it, “Arise,” and it arose; then he said to it, “Go back,” and it retreated; then he said to it, “Come forward,” and it approached; then he said to it, “Sit,” and it sat. Then he said: “I did not create [anything] that is better than you, nor nobler than you, nor more excellent than you, nor goodlier than you; through you I take, and through you I give, and through you I am known, and through you I punish; the reward is yours and the punishment is upon you.””

According to the Sunnī Hadith critic Ibn ʿAdī (d. 365/976), however, “weakness (al-ḍaʿf) is evident in what [al-Faḍl] transmitted.” Ibn ʿAdī stated this immediately after citing this hadith specifically – clearly, he regarded it to be weak. Likewise, according to the Sunnī Hadith critic Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597/1201), “this is a hadith that is not authentic (lā yaṣiḥḥu) from the Messenger of God.” As evidence therefor, he cited the judgements of past Hadith critics, e.g., Ibn Maʿīn (d. 233/848): “Al-Faḍl is a man of evil (rajul sūʾ).” However, Ibn al-Jawzī also impugned key tradents after al-Faḍl, citing Ibn Ḥibbān (d. 354/965): “Ḥafṣ b. ʿUmar transmits fabrications (al-mawḍūʿāt); reliance upon him in argumentation is impermissible.” Likewise, according to Ibn al-Jawzī himself, Sayf is “a liar according to the consensus of [the Hadith critics] (kadhdhāb bi-ijmāʿi-him.” Ibn al-Jawzī presumably sought to deny that the venerable Sufyān al-Thawrī had transmitted a fabricated hadith—thus, he calls into question Sayf’s transmission from Sufyān, despite the fact that Sayf’s transmission via Sufyān unto al-Faḍl is seemingly corroborated by Ḥafṣ.

To be charitable, Ibn al-Jawzī may simply have been following the standard early Sunnī Hadith-critical method of appealing to corroboration by great figures. If a tradent transmitted something from a great master, but the famous students of said great master did not also transmit, then that was taken to be a sign of unreliability on the part of the isolated tradent, all else being equal. In this case, only Sayf transmitted this hadith from Sufyān: the latter’s notable students, such as Qabīṣah and al-Firyābī, are nowhere to be seen.

It is certainly conceivable that Ḥafṣ is the real CL, and that Sayf borrowed the hadith from him (or one of his students) and dived around him (via a false ascription to Sufyān) to reach back to Ḥafṣ’s cited source, al-Faḍl. However, it is also possible that Sufyān’s nephew had greater access or more exposure to his uncle than did Sufyān’s students (by dint of being kinsmen). It is thus at least conceivable that Sayf alone heard certain hadiths from his uncle. Still, it does seem highly suspicious that no one else appears to have transmitted this hadith from such a prolific Hadith scholar – there are thus valid reasons to doubt Sayf’s ascription via Sufyān.

In short, on a pure ICMA, there would be no reason to doubt that al-Faḍl is a genuine CL; but when historical-contextual information is taken into account, his position is shaken. We might thus conclude that al-Faḍl is a potential CL, whilst his student Ḥafṣ is a more definite CL.

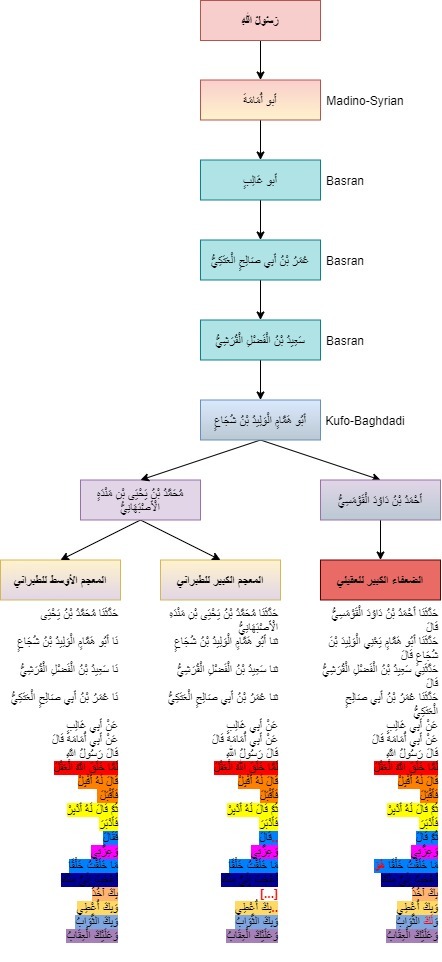

Part 2: The tradition of al-Walīd

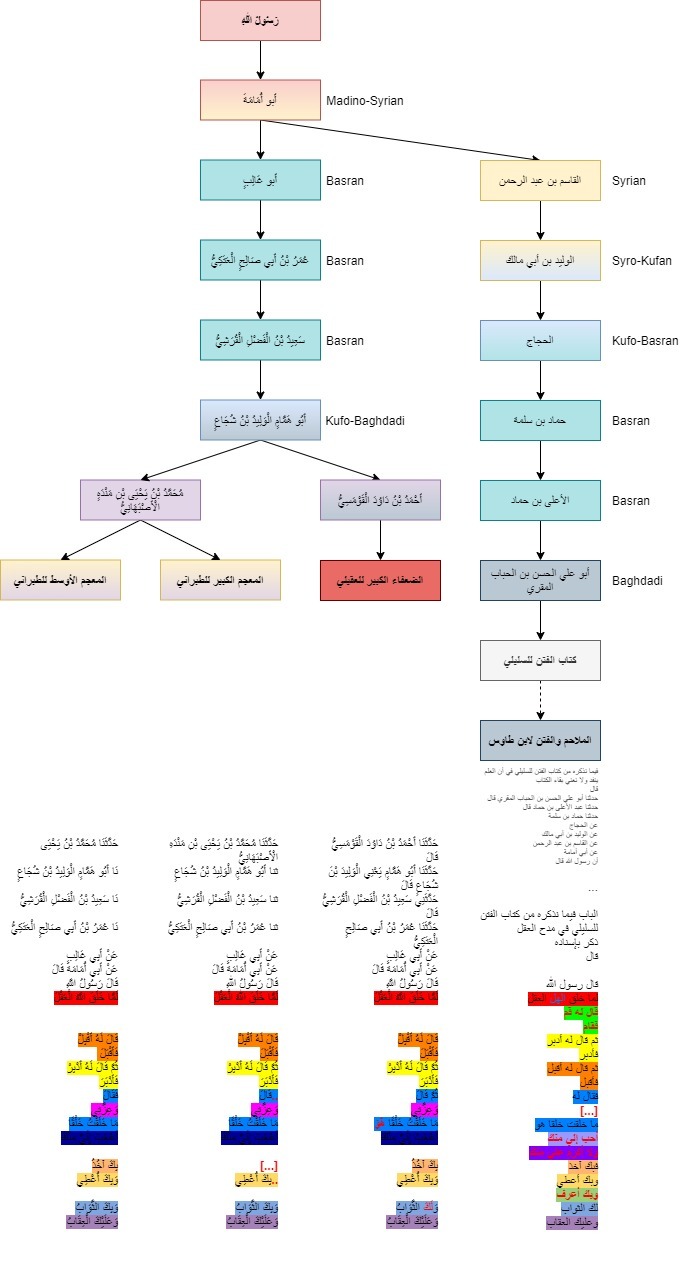

Another cluster of versions of this hadith claim to derive from al-Walīd b. Shujāʿ (Kufo-Baghdadi, d. 243/857), from a string of Basrans (Saʿīd b. al-Faḍl, from ʿUmar b. Abī Ṣāliḥ, from Abū Ghālib), from Abū Umāmah (Madino-Syrian, d. 86/705-706), from the Prophet.

There are minor differences, but again, the matns are markedly more similar to each other than to all other versions: al-Walīd is probably a genuine CL, whose distinctive redaction is shared by these extant versions. The following can thus be attributed to him:

al-Walīd b. Shujāʿ (Kufo-Baghdadi, d. 243/857): "Saʿīd b. al-Faḍl al-Qurashī related to us/me: “ʿUmar b. Abī Ṣāliḥ al-ʿAtakī related to us, from Abū Ghālib, from Abū Umāmah, who said: “The Messenger of God said: “When God created the Intellect, he said to it, “Come forward,” and it approached; then he said to it, “Go back,” and it retreated. Then he said: “By my power! I did not create [anything] more pleasing to me than you; through you I take, and through you I give; the reward is yours and the punishment is upon you.””

However, Ibn al-Jawzī was having none of it: “This is a hadith that is not authentic (lā yaṣiḥḥu) from the Messenger of God.” Again, Ibn al-Jawzī cited earlier Hadith critics, e.g., Ibn Ḥanbal (d. 241/855): “This hadith is fabricated (mawḍūʿ). It has no basis (laysa la-hu aṣl).” Similarly, al-ʿUqaylī (d. 322/933-934) declared: “There is nothing reliable (lā yathbutu) in this matn.” Rather than accusing the CL al-Walīd for having fabricated it, however, Ibn al-Jawzī blamed his sources: “Saʿīd, ʿUmar, and Abū Ghālib are unknowns (majhūlūn) [who are] rejected in Hadith (munkarū al-ḥadīth), and no one corroborated them in their Hadith.”

The earlier Hadith critic al-Ṭabarānī (d. 360/971) may have suspected the CL al-Walīd, stating: “This hadith is not transmitted from Abū Umāmah except by this isnad. Abū Hammām [al-Walīd] transmitted it in isolation (tafarrada bi-hi).” As Melchert notes, for Hadith critics, isolated transmission “is usually a sign that something is wrong.”

In this instance, however, al-Ṭabarānī appears to be mistaken: there is in fact an alternative isnad all the way back to Abū Umāmah, recorded by the Shīʿī Hadith scholar Ibn Ṭāwūs (d. 664/1266). Does this mean that we have a Companion CL?

It does not appear to be the case. This is because Al-Walīd and Ibn Ṭāwūs’ respective ascriptions via Abū Umāmah are in fact markedly more similar to other versions than they are to each other: the former is closer to al-Ṣādiq’s version (see below), whilst the latter is closer to al-Faḍl’s version (see above).

This is consistent with extreme contamination at best and false ascription at worse. We thus cannot identify Abū Umāmah as a genuine CL, at least not on the basis of an ICMA.

Additionally, Ibn Ṭāwūs’ version claims to derive via Ḥajjāj b. Arṭāh (Kufo-Basran, d. 149/766-767), who just so happens to have been remembered as a mudallis (i.e., someone who interpolated or tampered with isnads—e.g., omitting unreliable tradents). We thus might identify Ḥajjāj as responsible for creating this false parallel transmission from Abū Umāmah, although there is currently no way to confirm this.

Part 3: Abū Nuʿaym’s SS to the Prophet

Another version of this hadith is recorded in the Ḥilyah of Abū Nuʿaym (d. 430/1038), with a lengthy Mecco-Kufo-Madinan “single strand” (SS) isnad back to the Prophet.

This is a rather late source, and its wording is also unusual: “The first of that which God created was the Intellect (awwal mā khalaqa allāh al-ʿaql).” According to Abū Nuʿaym himself, this hadith is “strange [i.e., uncorroborated] (gharīb) amongst the Hadith of Sufyān [b. ʿUyaynah]. […] I do not know of anyone who transmitted it from al-Ḥumaydī except for Sahl, and I believe that he is the one who erred therein.” In other words, despite Sufyān’s stature, only al-Ḥumaydī allegedly transmitted it from him; and despite al-Ḥumaydī’s stature, only Sahl transmitted it from him; again, this was taken to be a sign that something was wrong.

The Ḥanbalī and Atharī titan Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 728/1328) was more emphatic in his denunciation of this hadith, which was used by Neoplatonist philosophers and others whom he regarded as heretics:

"It is known that the hadith that relates “the first of that which God created was the Intellect” (awwalu mā khalaqa allāh al-ʿaqlu) is an invalid (bāṭil) hadith from the Prophet. Even if it were true, it would be a proof against them, for verily its wording, “when God first created the Intellect” (awwala mā khalaqa allāh al-ʿaqla), is [actually] with an accusative awwala in the time-and-place adverb state (ʿalā al-ẓarfiyyah). …then he said to it: “Come forward,” and it approached; then he said to it, “Go back,” and it retreated; then he said: “By my power! I did not create [anything] more precious to me than you: through you I take, and through you I give; the reward is yours and the punishment is yours.” And it was [also] transmitted [in the form], “When God created the Intellect” (lammā khalaqa allāh al-ʿaqla). Thus, were the hadith authentic, its meaning would be that [God] addressed the Intellect in the first moments of its creation, and that he created other things before it, and that [only] these four things [i.e., taking, giving, reward, and punishment] occur through it, not all creations."

Ibn Taymiyyah does not specify that he means the version specifically cited by Abū Nuʿaym, but his generalisation would seem to apply thereto nevertheless.

Likewise, the great Sunnī Hadith scholar Ibn Ḥajar (d. 852/1449) declared: “The [more definitive statement] concerning the first of that which God created is the hadith: “The first of that which God created was the pen.” It is more reliable (athbat) than the hadith of the Intellect.”

Finally, the Sunnī Hadith scholar al-ʿIrāqī (d. 806/1403) addressed Abū Nuʿaym’s version directly: “Al-Ṭabarānī [cited it] in al-Awsaṭ amongst the Hadith of Abū Umāmah, and Abū Nuʿaym [cited it] amongst the Hadith of ʿĀʾishah, [both] with weak (ḍaʿīfayn) isnads.”

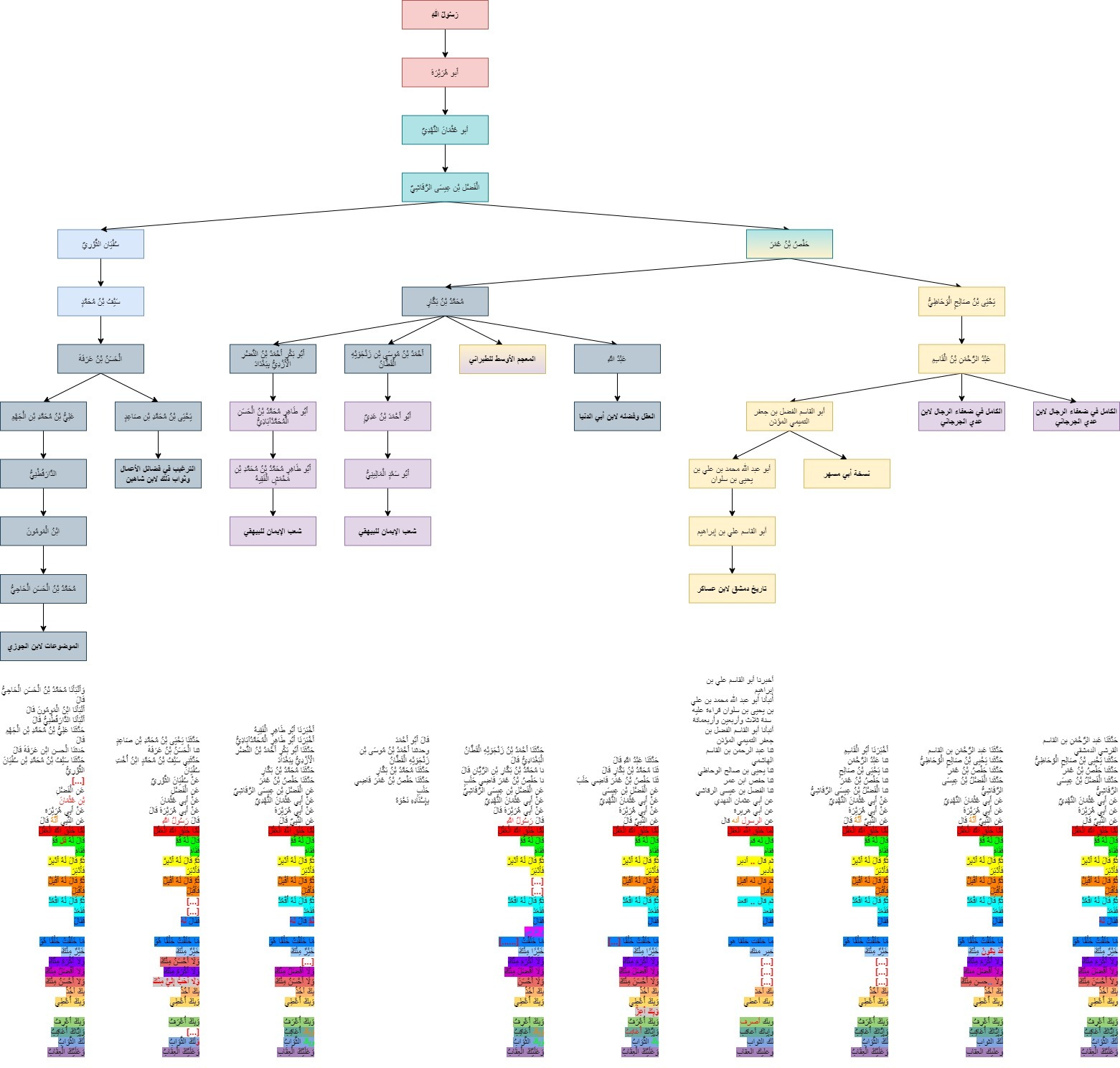

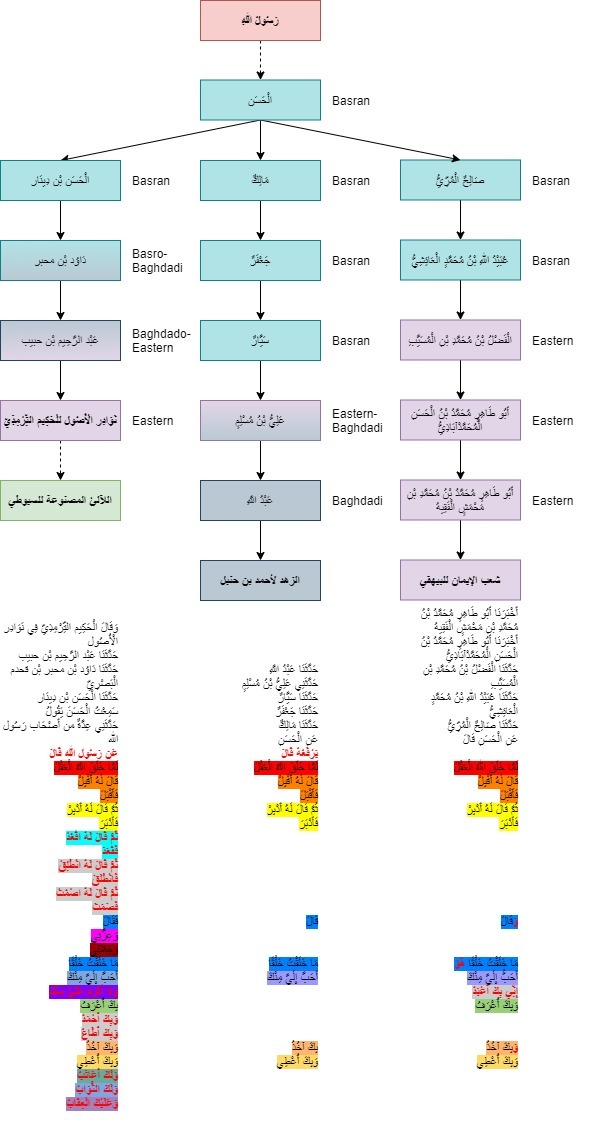

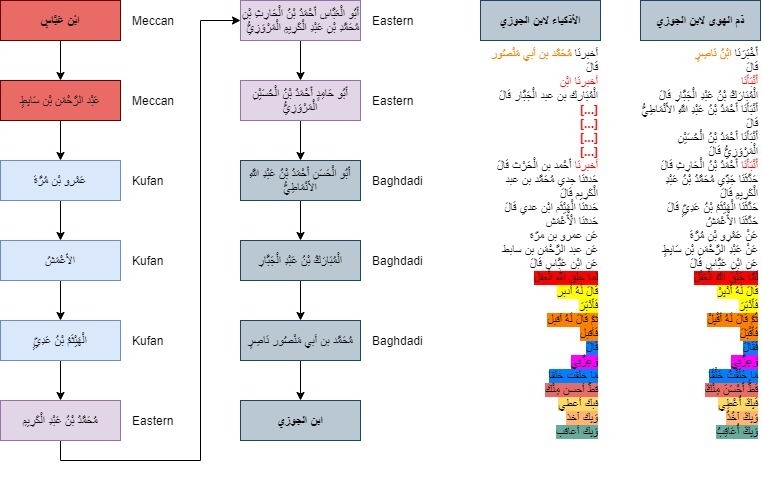

Part 4: The tradition of Ḥasan al-Baṣrī

Another cluster of versions claim to derive—via three Basran isnads—from the Basran Follower, ascetic (zāhid), and Qadarī Ḥasan (d. 110/728): one via Dāwūd b. al-Muḥabbar (Basro-Baghdadi, Ṣūfī, d. 206/821), from al-Ḥasan b. Dīnār (Basran, Qadarī, fl. 8th C. CE), from Ḥasan; one via Sayyār b. Ḥātim (Basran, zāhid, d. 199-200/814-816), from Jaʿfar b. Sulaymān (Basran, soft Shīʿī, d. 178/794-795), from Mālik b. Dīnār (Basran, bārr, d. 127-130/744-748), from Ḥasan; and one via ʿUbayd Allāh al-ʿĀʾishī (Basran, Qadarī, d. 228/ 842-843), from Ṣāliḥ al-Murrī (Basran, wāʿiẓ, qāṣṣ, zāhid, Qadarī, d. 172-176/788-793), from Ḥasan. The isnads therefor are lengthy SSs, which is somewhat suspect – he could be the target of successive borrowings and false ascriptions.

One of these versions (recorded by al-Ḥakīm al-Tirmidhī and al-Suyūṭī) clearly diverges from the other two, and is in fact more similar in several key respects to the versions of al-Faḍl, al-Ṣādiq, and al-ʿAlāʾ.

This is consistent with this version’s being contaminated thereby, and/or a dive derived therefrom. This is further consistent with al-ʿIrāqī’s highly critical comments thereon, albeit based on tradent-critical rather than ICMA grounds:

"All of its transmitters are irredeemable (halkā), except for al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrī. ʿAbd al-Raḥīm b. Ḥabīb al-Fāryābī is nothing (laysa bi-shayʾ)—Yaḥyā b. Maʿīn said that; and Ibn Ḥibbān said: “He potentially fabricated (waḍaʿa) more than 500 Hadith.” Dāwūd was addressed previously. Al-Ḥasan b. Dīnār is weak (ḍaʿīf) also."

As for Dāwūd b. al-Muḥabbar, Ibn al-Jawzī reported:

"Dāwūd b. al-Muḥabbar. Aḥmad [b. Ḥanbal] and al-Bukhārī said: “He is like nothing (shibh lā shayʾ).” Ibn al-Madīnī said: “His Hadith are far gone (dhahaba).” Abū Ḥātim al-Rāzī said: “Not reliable (ghayr thiqah).” Al-Dāraquṭnī said: “Abandoned (matrūk).” Ibn Ḥibbān said: “He used to fabricate (kāna yaḍaʿu) Hadith unto reliable tradents (ʿalā al-thiqāt).”

Likewise, in relation to this particular hadith, the Egyptian Hadith scholar al-Sakhāwī (d. 902/1497) declared: “Ibn al-Muḥabbar was a liar (kadhdhāb).”

By contrast, the matns of the other two ascriptions to Ḥasan are markedly more similar to each other than to all the rest, which means that it is at least plausible that Ḥasan is a genuine CL, whose distinctive redaction is reflected in common in these two transmissions.

The following ur-version can thus be tentatively attributed to Ḥasan (bearing in mind that we are still dealing with merely two SSs):

Ḥasan al-Baṣrī (d. 110/728): “When God created the Intellect, he said to it, “Come forward,” and it approached; then he said to it, “Go back,” and it retreated. He said: “I did not create [anything] more beloved to me than you; [verily through you I am worshipped, and through you I am known, and] through you I take, and through you I give.”

However, in addition to some notable additions/omissions in the matns, there is a major difference between these two versions: one (recorded by al-Bayhaqī) claims to be merely the words of Ḥasan himself (“from al-Ḥasan, who said”), whereas the other (recorded by ʿAbd Allāh b. Aḥmad) depicts Ḥasan as attributing the words all the way back to the Prophet (“from al-Ḥasan, who ascribed it back to the Prophet (yarfaʿu-hu), who said”). Meanwhile, the interpolated/contaminated ascription to Ḥasan (recorded by al-Suyūṭī) takes it a step further by vaguely asserting that Ḥasan received this hadith from a number of Companions, who in turn received it from the Prophet: “I heard al-Ḥasan say: “A number of the Companions of the Messenger God related to me from the Messenger of God, who said…” Based on the Criterion of Dissimilarity, and the known tendency for early Muslims to prefer Prophetical Hadith over non-Prophetical Hadith, it seems much more likely that this hadith reflects Ḥasan’s words, and that the Prophetical versions are secondary.

The Sunnī Hadith scholar al-Bayhaqī (d. 458/1066) seemingly came to a similar conclusion (albeit via different means): “This is from the speech of al-Ḥasan and someone other than him; [it is] famous; it has been transmitted from the Prophet with an isnad that is not strong (ghayr qawī).” However, the later Sunnī Hadith scholar al-Suyūṭī (d. 911/1505) apparently regarded a Prophetical version of this hadith to be authentic, despite the fact that it is mursal (i.e., Ḥasan cited no intermediary Companion sources unto the Prophet):

“"The hadith of “When God created the Intellect, he said to it, “Come forward,” and it approached; then he said to it, “Go back,” and it retreated. Then he said: “I did not create [anything] nobler than you: through you I take, and through you I give” is false (kadhib), fabricated (mawḍūʿ), by agreement (bi-al-ittifāq). Al-Zarkashī corroborated Ibn Taymiyyah thereon. [However,] I have found that it has a sound source (aṣlan ṣāliḥan). ʿAbd Allāh, the son of Imam Aḥmad, reported it in [his] additions [to his father’s Kitāb] al-Zuhd. He said: “ʿAlī b. Muslim related to us: “Sayyār related to us: “Jaʿfar related to us: “Mālik b. Dīnār related to us, from al-Ḥasan, who ascribed it back to the Prophet (yarfaʿu-hu): “When God created the Intellect, he said to it, “Come forward,” and it approached; then he said, “Go back,” and it retreated. He said: “I did not create [anything] more beloved to me than you: through you I take, and through you I give.” This is mursal, [but still] good (jayyid) [in terms] of the isnad. And it is in the Muʿjam al-Ṭabarānī al-Awsaṭ as a mawṣūl [i.e., with an unbroken isnad], amongst the Hadith of Abū Umāmah, and amongst the Hadith of Abū Hurayrah, [both] with weak (ḍaʿīfayn) isnads."

As Douglas Crow notes, it seems like “al-Suyūṭī was inclined to accept al-Ḥasan’s irsāl” (i.e., his broken transmission from the Prophet). Apparently, al-Zabīdī (d. 1205/1790) also concurred.

However, as al-Suyūṭī’s contemporary al-Sakhāwī noted, this version derives via “Sayyār b. Ḥātim, who was amongst those who have been declared weak (ḍaʿʿafa-hu) by more than one [scholar]”. It would thus seem that al-Sakhāwī regarded this version to be suspect.

Finally, Crow seems to accept that the mursal hadith genuinely goes back to either Mālik b. Dīnār or Ḥasan al-Baṣrī, but likewise rejects the raised versions that claim to reach all the way back to the Prophet as ahistorical and interpolated.

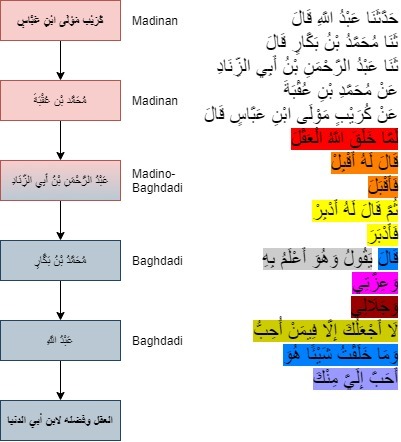

Part 5: The SS to Kurayb

Another version of the hadith claims to derive via a Baghdado-Madinan SS from the Madinan Follower Kurayb (d. 98/716-717).

The matn of this version is most similar to those ascribed to the Shīʿī imams, which is interesting: both Kurayb and the imams were Madinan, such that there appears to be a correlation between Madinan Follower-sources and a particular set of wordings.

I have not found any parallel transmissions of this ascription to Kurayb, so it cannot be traced back to any particular early tradent in the isnad, at least on ICMA grounds.

I was also unable to find any traditional Sunnī judgements on this version, although something can be said about Ibn Abī al-Zinād (d. 174/790-791), the one who brought this hadith from Madinah to Baghdad (according to the isnad). Although he was regarded by some to be “reliable” (thiqah), Ibn Abī al-Zinād was also regarded as “such and such” (kadhā wa-kadhā), “muddled” (muḍṭarib), “nothing” (laysa bi-shayʾ), “weak” (ḍaʿīf), and someone who “cannot be relied upon in argumentation” (lā yaḥtajju bi-hi). More importantly, several Hadith critics declared that Ibn Abī al-Zinād specifically became less reliable or unreliable when he moved from Madinah to Baghdad—and, as it happens, this Kurayb hadith was ostensibly only transmitted by Ibn Abī al-Zinād in Baghdad.

Part 6: The SS to Ibn ʿAbbās

Another version of the hadith (recorded in two of Ibn al-Jawzī’s works) claims to derive via a Baghdado-Eastern-Kufo-Meccan SS back to the Companion Ibn ʿAbbās (d. 67-68/686-688).

The matn is in some ways close to al-Walīd’s version (see above), and in other ways close to the Shīʿī versions (see below). However, I have not found any parallel transmissions of this version, so it cannot be traced back to any particular early tradent in the isnad, at least on ICMA grounds.

I have also found no traditional Hadith judgements thereon, although Crow maintains that Ibn al-Jawzī’s inclusion of this version in two of “his moralizing and didactic works is noteworthy, since one of his missions in life was to purify the body of ḥadīth from falsities and weak reports.” Still, this is a far cry from any kind of explicit approval, and the ascription to Ibn ʿAbbās remains oddly uncorroborated, by both Meccans and Kufans, despite its alleged Meccan and Kufan provenance.

Something more can be said about one of the putative Kufan transmitters of this hadith: Sulaymān b. Mihrān al-Aʿmash (a soft Shīʿī, d. 147-148/764-766). Although he was regarded as “reliable” (thiqah, thabt) by several later Sunnī Hadith critics, Ibn Ḥanbal also reported that there was “a lot of confusion” (iḍṭirāb kathīr) in his Hadith and Ibn Ḥibbān reported that he was some kind of “deceiver” (mudallis) in Hadith. According to the later Sunnī Hadith scholar al-Dhahabī (d. 748/1348), “al-Aʿmash was a proof (ḥujjah), a great scholar (ḥāfiẓ), but he [nevertheless] deceptively transmitted from unreliable tradents (yudallisu ʿan al-ḍuʿafāʾ).” Harsher still were the early Hadith transmitters al-Mughīrah b. Miqsam al-Ḍabbī (Kufan, d. 132-134/749-752) and ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Mubārak (Khurasanian, d. 181/797), both of whom reportedly declared that al-Aʿmash had “corrupted” (afsada) the Hadith of Kufah. If such judgements and reports are anything to go by, then the transmission of this hadith—its claim to derive all the way back from Ibn ʿAbbās—is suspect.

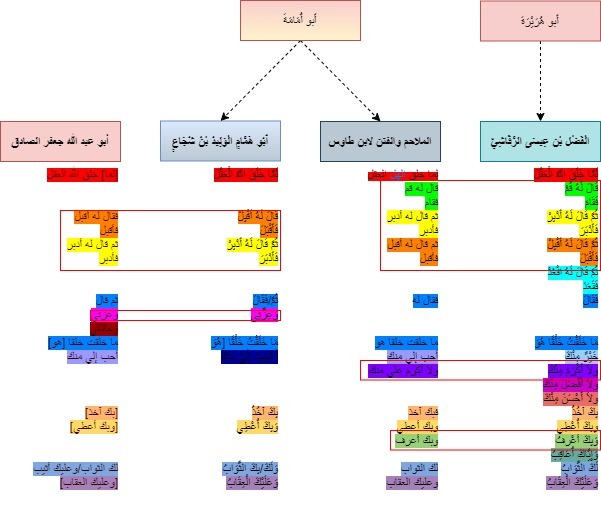

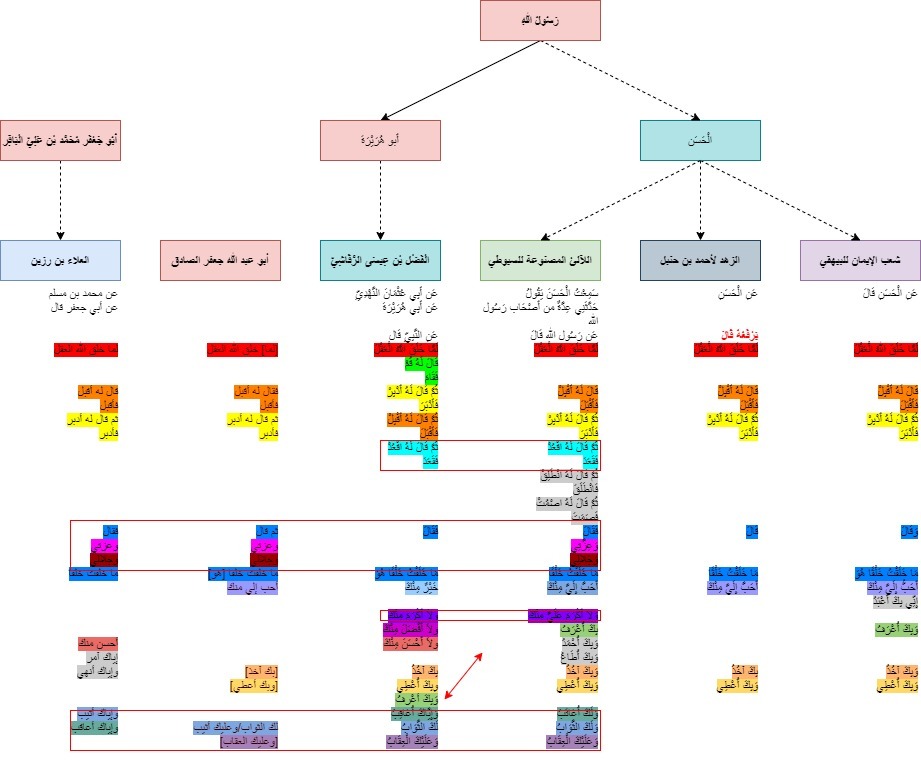

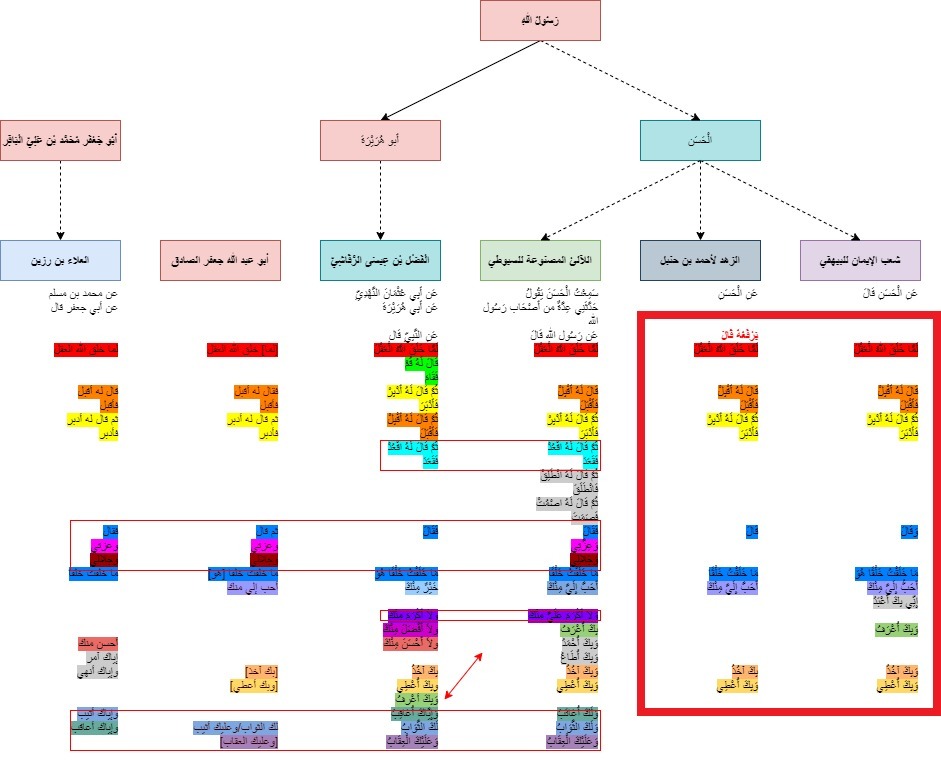

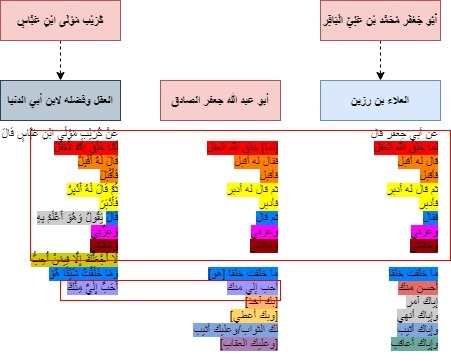

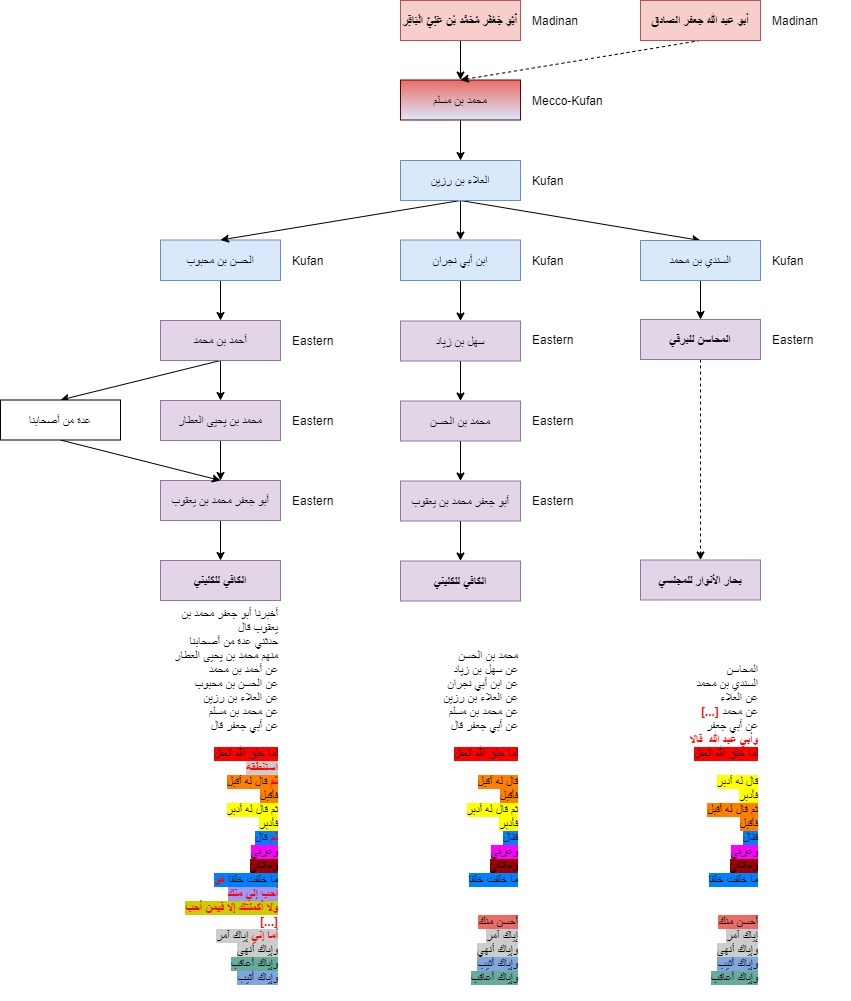

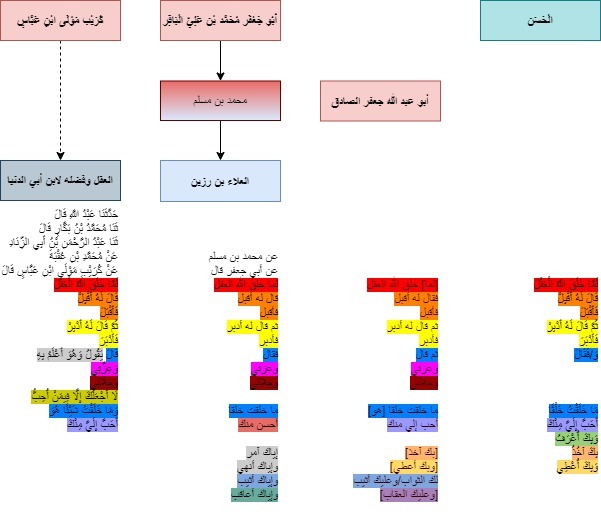

Part 7: The tradition of al-ʿAlāʾ

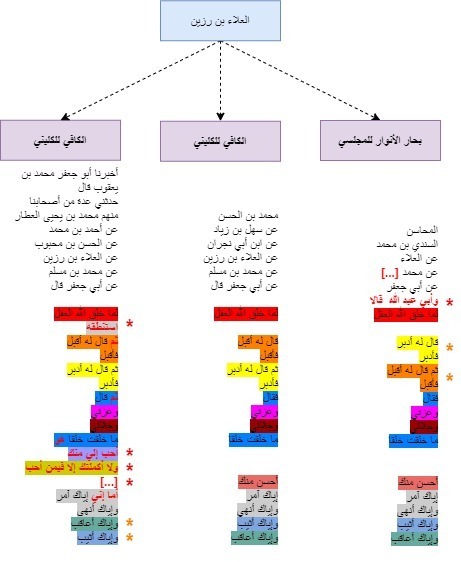

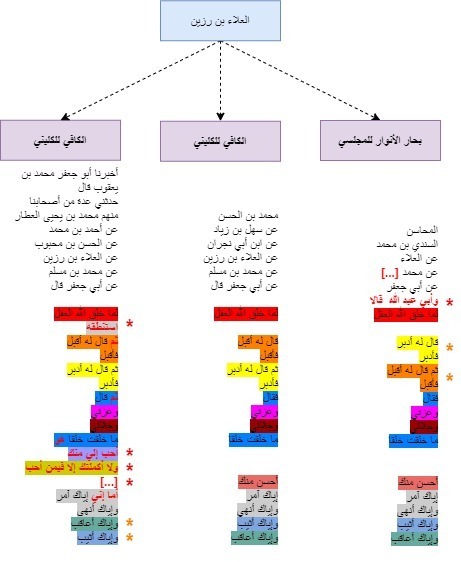

Another cluster of versions claims to derive via three Kufans from al-ʿAlāʾ b. Razīn (Kufan, hard-line Shīʿī, fl. late 8th C. CE), from Muḥammad b. Muslim (Mecco-Kufan, hard-line Shīʿī, d. 150/767), from the Shīʿī imam (and Follower) Muḥammad al-Bāqir (Madinan, d. 114/732-733, or 117/735).

One version of this hadith is obviously altered and contaminated in its matn (for which the hard-line Shīʿī Kufan tradent al-Ḥasan b. Maḥbūb, or someone after him, must responsible), but all three are still largely more similar to each other than they are to all the rest, which is consistent with al-ʿAlāʾ’s being a genuine CL, whose distinctive redaction is embodied thereby.

In fact, by comparing these three extant versions, it appears that one of them (transmitted by the hard-line Kufan Shīʿī tradent Ibn Abī Najrān and recorded by al-Kulaynī) is perfectly preserved, being identical with the inferable urtext from al-ʿAlāʾ. Thus, the following can be attributed to al-ʿAlāʾ:

al-ʿAlāʾ b. Razīn (fl. late 8th C. CE): "…from Muḥammad b. Muslim, from Abū Jaʿfar, who said: “When God created the Intellect, he said to it, “Come forward, and it approached; then he said to it, “Go back,” and it retreated. He said: “By my power and my majesty! I did not create [anything] better than you; through you I command and through you I forbid, and through you I reward, and through you I punish.””

Additionally, one version ascribes the hadith to both al-Bāqir and his son al-Ṣādiq, where the other two ascribe it only to al-Bāqir. Clearly, they represent al-ʿAlāʾ’s original ascription, whilst the odd one out was interpolated or otherwise altered after al-ʿAlāʾ.

Ironically, the version with a matn that is obviously altered and contaminated (transmitted by al-Ḥasan b. Maḥbūb) was judged to be “authentic” (ṣaḥīḥ) by the leading Twelver Hadith scholar ʿAllāmah Majlisī (d. 1110/1699), whilst the version that seems to most accurately reflect al-ʿAlāʾ’s original (transmitted by Ibn Abī Najrān) was judged to be “weak” (ḍaʿīf).

Part 8: The tradition of al-Ṣādiq:

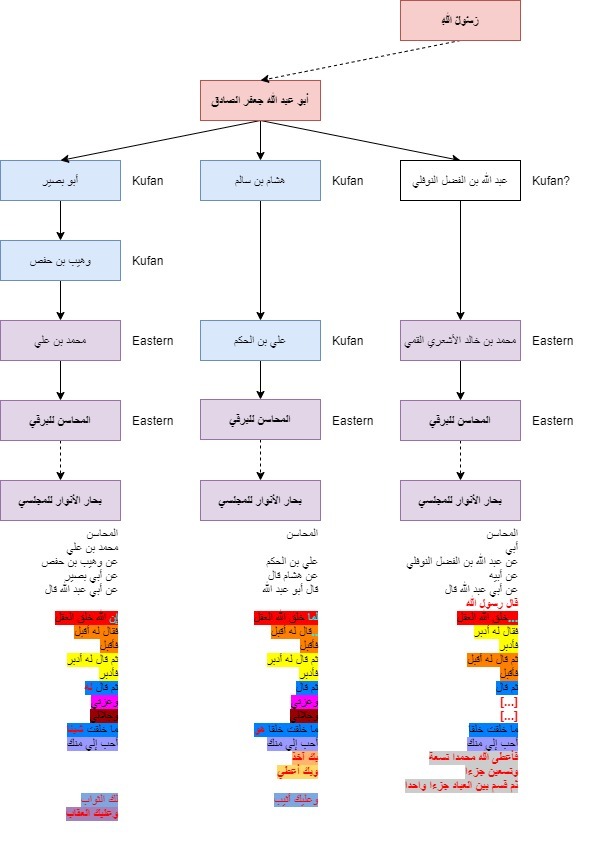

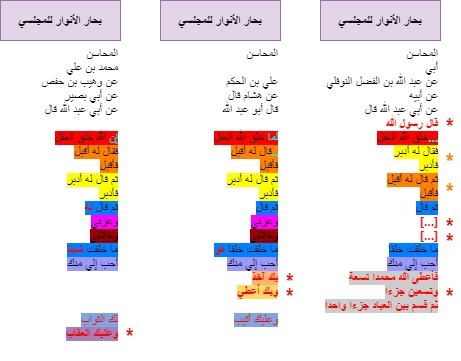

Another cluster of versions are ascribed via three Eastern-Kufan hard-line Shīʿī SSs unto the Shīʿī imam (and Follower of the Followers) Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq (Madinan, d. 148/765).

There are notable discrepancies between their matns, and one of them even depicts al-Ṣādiq citing the Prophet (for which the subsequent tradents ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Faḍl or Muḥammad b. Khālid al-Ashʿarī are presumably responsible). Despite this, at least two of them are more similar to each other than they are to the rest, which is consistent with their reflecting a common underlying redaction from their cited source. Even the third version has some notable similarities, though also being highly divergent.

Al-Ṣādiq is thus plausibly a genuine CL (despite only being reached by lengthy SSs), to whom the following is tentatively attributable:

al-Ṣādiq (d. 148/765): "[When] God created the Intellect, [then] he said to it: “Come forward, and it approached; then he said to it, “Go back,” and it retreated. He said: “By my power and my majesty! I did not create [anything] more beloved to me than you; [through you I take, and through you I give, and] upon you is the reward/through you I reward [and upon you is the punishment].”

Similarly (though without an ICMA), Crow concluded that “there is little reason to question this attribution to al-Ṣādiq.”

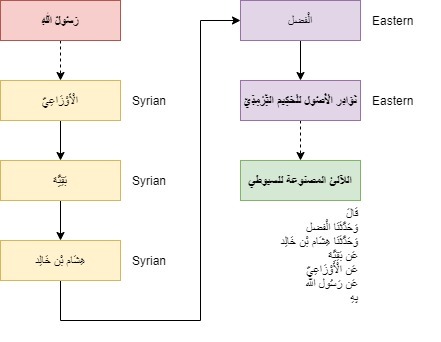

Part 9: The SS via al-Awzāʿī

Another version of the hadith is ascribed via an Eastern-Syrian SS from Hishām b. Khālid (Syrian, student of Damascene Murjiʾīs, d. 249/863-864), from Baqiyyah b. al-Walīd (Syrian, possibly Murjiʾī, anti-Qadarī, d. 197/812-813), from al-Awzāʿī (Syrian, anti-Murjiʾī, anti-Qadarī, ascetic, d. 156-157/772-774), who reportedly ascribed it in turn all the way back to the Prophet, but without any specified sources there-between. In other words, this version is mursal, if not worse.

Given the absence of a matn in this version, and given the absence of any corroborating transmissions, little more can be said about it. There is no way to know, for example, if the hadith even goes back to any Syrian sources, let alone al-Awzāʿī in particular, let alone all the way back to the Prophet. There is however a traditional judgement on this version: according to the Indian Sunnī Hadith scholar al-Muttaqī al-Hindī (d. 975/1567), “[the transmission of] al-Ḥakīm from al-Awzāʿī is muʿḍal [i.e., missing two consecutive tradents in the isnad].” For Sunnī Hadith critics, this rendered the hadith inadmissible.

Given that al-Awzāʿī was famously pro-Umayyad, anti-Qadarī, and also opposed to the Murjiʾī doctrine of faith, we have reason to doubt that this hadith—which was overwhelmingly associated with Shīʿīs, Qadarīs, Murjiʾīs, and other so-called heretics—actually derives from him. Instead, it seems more likely that a later tradent retrojected it via al-Awzāʿī, given his stature as a great transmitter of Hadith. If so, the most likely culprits therefor would be Baqiyyah, Hishām, or some other suppressed Syrian tradent, since it was above all Syrians who respected al-Awzāʿī (i.e., who had the strongest motive to invoke his authority). In the absence of further evidence, however, such a conclusion is tentative.

Part 10: ICMA back to the Prophet?

How far back can we trace this hadith? The only remaining apparent CL is the Prophet:

Even putting aside (1) the fact that many scholars agree that isnads largely arose a century after him, and (2) the fact that the pressure to create alternative, corroborating isnads would have been most intense for Prophetical hadiths (which became the fiercest battleground for intra-Islamic legitimacy at turn of the 9th Century CE), and (3) the fact that the Prophet is (somewhat suspiciously) only reached by lengthy SSs, the simple fact remains that the versions ascribed to the Prophet are not more similar to each other than they are to the versions ascribed to other figures:

- The Ḥafṣ/al-Faḍl ascription to the Prophet has the “adbir” element and then the “aqbil” element, like the ascription to Ibn ʿAbbās, whereas the other ascriptions to the Prophet, and every other version, have “aqbil” and then “adbir”.

- The Ḥafṣ/al-Faḍl ascription to the Prophet adds the “qum” and “uqʿud” elements, and also the “akram” and “afḍal” elements, absent from all other versions.

- Al-Walīd’s ascription to the Prophet has “wa-ʿizzatī”, like the ascriptions to Ibn ʿAbbās, Kurayb, and the Shīʿī imams, whereas the other ascriptions to the Prophet, and every other version, lack this element.

- Al-Walīd’s ascription to the Prophet has “aʿjab ilayya min-ka”, and Ḥafṣ/al-Faḍl’s has “khayr min-ka”, somewhat similar to the “aḥabb ilayya min-ka” of the versions of Ḥasan and al-Ṣādiq, and the ascription to Kurayb, whereas Abū Nuʿaym’s ascription to the Prophet jumps straight to “aḥsan min-ka”, like the ascriptions to Ibn ʿAbbās and al-Bāqir.

- Al-Walīd’s ascription to the Prophet omits the “aḥsan” element, like the versions of Ḥasan and al-Ṣādiq and the ascription to Kurayb, whereas the other two ascriptions to the Prophet, and every other version, have this element.

- The Ḥafṣ/al-Faḍl ascription to the Prophet adds the “uʿrafu” element, like Ḥasan’s version, whereas the other two ascriptions to the Prophet, and every other version, lack this element.

- The Ḥafṣ/al-Faḍl ascription to the Prophet adds the “uʿāqibu” element, like the ascriptions to Ibn ʿAbbās and al-Bāqir, whereas the other two ascriptions to the Prophet, and every other version, lack this element.

- Ḥafṣ/al-Faḍl and al-Walīd’s ascriptions to the Prophet share the “thawāb” and “ʿiqāb” elements, as does al-Ṣādiq’s version; the ascription to al-Bāqir also shares the first element; but Abū Nuʿaym’s ascription to the Prophet omits them, like all other versions.

- Abū Nuʿaym’s ascription to the Prophet adds two other narrations onto the end of the hadith, absent in all other versions.

In short, there is no distinctive, underlying redaction that correlates with ascriptions to the Prophet vis-à-vis other early figures – we have no ICMA grounds for attributing this hadith to the Prophet (again, even putting aside the further confounding factors mentioned above).

This is broadly consistent with most of the traditional Sunnī judgements on this hadith. As we have already seen, Ibn Taymiyyah declared thereon in general: “Verily it is false (kadhib), fabricated (mawḍūʿ), by agreement (bi-ittifāq).”

Part 11: Form criticism

We have reached the limits of the ICMA: there are no earlier CLs to analyse, other than the Prophet, who cannot be established as such. What more can be said about these hadiths, then?

Form criticism may be of service here. Even without isnads, the patterns of the matns can tell us something about the hadith’s history. In this case, it should be clear now that, despite all the variation that we have encountered, this is a single hadith. In other words, these are not merely multiple different hadiths addressing the same topic: all of these hadiths are clearly variants of the same underlying tradition, sharing as they do a common, underlying form. All of them start with the creation of the Intellect, then depict God commanding it to move around, then depict God stating that this is the best thing that he created. There is no way that several figures could have created this independently of each other.

In other words, we have a situation in which a short theological story is depicted as being the words of several different people, when it can only be the words of a single person. How do we explain this?

Part 12: Analysing ascription types

One hyper-sanguine explanation would be that the Prophet uttered the ur-version of this hadith, and that some later figures—Ibn ʿAbbās, Ḥasan, Kurayb, al-Bāqir, and al-Ṣādiq—simply repeated his statement without crediting him. Thereafter, the hadith was subject to mutation and contamination in the course of transmission, resulting in all of the variations discussed above. However, the original Prophetical ascription was retained in some versions that reached us.

This seems dubious to me—a simple explanation would be that the ascription to the Prophet is a secondary development. This would also conform to our established background knowledge on the common occurrence of ‘raising’ (rafʿ) in Hadith, along with the general Islamic legal and theological tendency towards preferring Prophetical hadiths over others, which predominated around the turn of the 9th Century or soon thereafter. Similar reasoning can be applied to the ascription to Ibn ʿAbbās, a Companion, vis-à-vis the versions ascribed to Followers: the former is probably secondary (in which case, the Prophetical versions are actually tertiary).

Here is another way of looking at it. Since all of these hadiths are actually versions of the same report, the question arises: which has the strongest claim to representing the original ascription? Was the hadith actually ascribed to the Prophet, or a Companion, or a Follower? Given the background evidence outlined above, it is much more likely that an ascription to a later figure was reformulated as an ascription to an earlier figure, rather than vice versa. The reverse would simply be to downgrade the value of the hadith, running directly against the increasing prioritisation of Companion and then Prophetical hadiths over the late 8th and early 9th Centuries. In other words, the Follower versions of the hadith are more likely to be the most archaic, since anyone creating/altering the hadith in the late 8th and early 9th Centuries would likely want to ascribe it to earlier, more authoritative sources (i.e., Companions, then the Prophet). In short, the Criterion of Dissimilarity favours the Follower versions of the hadith as more likely to reflect the original, vis-à-vis Companion and Prophetical versions.

Perhaps a similar kind of reasoning was used by the early Sunnī Hadith critics who rejected the Prophetical versions of this hadith. Unfortunately, they are often quite opaque when it came to the reasoning behind specific judgements, so it is hard to know.

Crow likewise agrees that the ascriptions to the Prophet are “extremely improbable”, and that the ascriptions to Companions are “alleged” and “symbolic” (i.e., dubious). Additionally, Josef van Ess seems to have specifically doubted al-Faḍl’s ascription via Abū ʿUthmān and Abū Hurayrah back to the Prophet.

All of this leaves us with the Follower versions of the hadith. As we have seen, two of these are plausibly genuine: the version of the famous Basran ascetic Ḥasan (d. 110/728), and that of the Madinan imam al-Ṣādiq (d. 148/765), who is actually a Follower of the Followers. By contrast, the other two Follower versions are uncorroborated ascriptions, to Kurayb (d. 98/716-717) and the imam al-Bāqir (d. 114/732–733, or 117/735), both of whom are Madinans.

Van Ess stated that the ascription to Kurayb is possibly genuine (“vielleicht echte”), but did not elaborate thereon (to the best of my knowledge). By contrast, Crow argued that one of the versions ascribed to al-Bāqir is authentic, because it states that God “interrogated” the Intellect, which fits “a well-established motif common in the first century (see n. 133) of testing a person’s ʿaql”. Crow at least provides an argument (in contrast to Van Ess on Kurayb), but one that is unconvincing, for two reasons. Firstly, Crow’s basis for the 1st-Century AH provenance of his cited motif amounts to little more than an uncritical acceptance of a story about Yazīd b. Muʿāwiyah (r. 680-683), and another about Sulaymān b. ʿAbd al-Malik (r. 715-717). Secondly, on ICMA grounds (as we have already seen), the version that Crow is citing—including the interrogation element—is clearly interpolated or contaminated, when compared to the two parallel transmissions from the common source of all three, the CL al-ʿAlāʾ.

Thus, not only can Crow’s cited version and motif not be traced back to al-Bāqir, they cannot even be traced back to the later CL al-ʿAlāʾ.

We are thus still left with two plausible ascriptions (Ḥasan, al-Ṣādiq) and two uncorroborated and unconfirmed ascriptions (Kurayb, al-Bāqir), amongst the Followers at the end of the 1st Century and the beginning of the 2nd Century AH.

Part 13: Geographical analysis of isnads

Is there any other way to evaluate these ascriptions? The geography of the isnads can provide a clue. Nearly all versions of this hadith claim to derive from Madinan sources, yet every single one derives via Iraqi sources, bar one alleged Syrian SS.

This is remarkably odd: if indeed this hadith originated amongst various notable figures in 1st-Century AH Madinah, why was it only preserved in Iraq? This is a reason to suspect that the hadith actually originated in Iraq and was merely ascribed back to Madinan sources. Moreover, as it happens, the earliest source back to whom this hadith can be plausibly traced is Ḥasan al-Baṣrī (d. 110/728), an Iraqi—and, as we have already established, he probably expressed it as his own statement.

Part 14: Conclusions

All of this allows us to sketch a provisional origins scenario for this hadith. Firstly, it was disseminated by the Qadarī ascetic Ḥasan in Basrah at the turn of the 2nd Century AH. Secondly, it rapidly spread in the Shīʿī, Qadarī, and ascetic milieu of Iraq at that time, mutating and acquiring additional elements all the while. Thirdly, it acquired parallel, ‘independent’ isnads and ascriptions as it spread and mutated in the 2nd Century: a hard-line Shīʿī in Kufah (plausibly al-ʿAlāʾ) ascribed it back to Imam al-Bāqir; another Kufan (plausibly the soft Shīʿī al-Aʿmash) ascribed it back to Ibn ʿAbbās; a Baghdadi (plausibly Ibn Abī al-Zinād) ascribed it back to Kurayb; and various Ṣūfīs, Qadarīs, and/or ascetics in Basrah (plausibly Sayyār b. Ḥātim, Jaʿfar b. Sulaymān, or Mālik b. Dīnār, in one case, and Dāwūd b. al-Muḥabbar or al-Ḥasan b. Dīnār, in another) raised Ḥasan’s version back to the Prophet, whilst other Basrans (plausibly Ḥafṣ b. ʿUmar or al-Faḍl b. ʿĪsā, in one case; Saʿīd b. al-Faḍl or ʿUmar b. Abī Ṣāliḥ, in another; and Ḥajjāj b. Arṭāh, in yet another) also created versions with ‘independent’ and unbroken isnads back to the Prophet. From Basrah the hadith spread to Syria, where a Murjiʾī (plausibly Hishām or Baqiyyah) created an ‘independent’ but broken isnad back to the Prophet. It may also have spread to Madinah by the middle of the 2nd Century, since a version is traceable back to Imam al-Ṣādiq (d. 148/765), a Madinan—but that said, he only disseminated it to Kufans, so it is plausible that he both acquired and spread it during his visits to Kufah. Finally, a subsequent hard-line Shīʿī (plausibly ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Faḍl or Muḥammad b. Khālid al-Ashʿarī) raised al-Ṣādiq’s version back to the Prophet, whilst an obscure—possibly Neoplatonist—figure of indeterminate provenance (probably Sahl b. Marzubān) created a version (“the first of that which God created was the Intellect”) with yet another ‘independent’ isnad back to the Prophet.

This reconstruction largely agrees with Crow, but differs on a key point: where Crow traces it back to the Followers of both Iraq and the Hijaz, I am skeptical that it can be traced back to the latter (i.e., to Kurayb and al-Bāqir). However, I am in full agreement with Crow (and most traditional Sunnī Hadith scholars, including Ibn Taymiyyah) that it cannot be traced back to the Companions or the Prophet, and that its ascription thereto is a secondary development. That said, Crow does not think that the Followers created this hadith out of thin air: instead, he argues that the concept underlying the hadith has its roots in pre-Islamic wisdom sayings, which gained articulation through some Followers; then, over successive generations, the Follower versions were altered and progressively retrojected back to the Companions and the Prophet. Thus, Crow is proposing that this hadith was created ex materia rather than ex nihilo, as it were.

The idea that many hadiths were fashioned out of—or evolved out of—pre-Islamic beliefs, stories, sayings, and other such material is well-established in secular scholarship, going back as early as Goldziher, e.g.:

"For not only law and custom, but theology and political doctrine also took the form of hadith. Whatever Islam produced on its own or borrowed from the outside was dressed up as hadith. In such form alien, borrowed matter was assimilated until its origin was unrecognizable. Passages from the Old and New Testaments, rabbinic sayings, quotes from apocryphal gospels, and even doctrines of Greek philosophers and maxims of Persian and Indian wisdom gained entrance into Islam disguised as utterances of the Prophet. Even the Lord's Prayer occurs in well-authenticated hadith form. This was the form in which intruders from afar became directly or indirectly naturalized in Islam."

In this particular case, however, Crow admits that his hypothesis is speculative (“possible and plausible”): this hadith may be a reworking of a pre-Islamic wisdom saying, or it may simply be the product of early Islamic theologising in Basrah.

Part 15: Summary

The hadith about God’s creation of the Intellect appears at first glance to be supported by a small forest of isnads, variously reaching back to Followers, Companions, and the Prophet. On closer inspection, however, most of these have proved to be suspect or false.

- An isnād-cum-matn analysis allowed us to reconstruct certain versions back to earlier figures (including the CL al-ʿAlāʾ, the CL Ḥafṣ, the CL al-Ṣādiq, and the Follower Ḥasan al-Baṣrī), but also exposed the falsity of other ascriptions back to other early figures (most notably, the Companion Abū Umāmah and the Prophet), not to mention frequent interpolations and alterations even in broadly authentic ascriptions.

- A form-critical analysis revealed that all of the extant versions of this hadith clearly derive from a single ur-hadith, despite their isnads presenting them as the utterances of various different early figures.

- An analysis of ascription types, employing the Criterion of Dissimilarity, revealed that the versions ascribed to Followers are probably more archaic than the versions ascribed to Companions and especially the Prophet.

- A geographical analysis of the isnads revealed that the hadith probably originated in Iraq (in particular, Basrah), despite the claims of most thereof to derive from Madinan sources.

- Altogether, these analyses reveal that this hadith probably originated with a Follower in Basrah around the turn of the 2nd Century, whence it spread to Iraq more broadly (and thence to Syria and the East), mutating and acquiring new and improved isnads as it proliferated amongst different sects.

- Most traditional Sunnī Hadith scholars rejected this hadith as weak or fabricated (at least as a Prophetical ascription), and although al-Suyūṭī seems to have accepted one version as authentic, he comes across as an outlier.

- Meanwhile, a leading traditional Shīʿī Hadith scholar judged one Shīʿī version—ascribed to Imam al-Bāqir—to be authentic and another to be weak, although this clashes with the results of my ICMA and other analyses.

- Finally, in a 1996 PhD thesis, Douglas Crow argued that the hadith originated amongst the Followers of both Iraq (which I affirm) and the Hijaz (which I doubt), deriving ultimately from pre-Islamic wisdom sayings (which is plausible but speculative).

For more on this hadith, and for an exploration of the various early sectarian uses and reworkings thereof, see Crow’s aforementioned PhD thesis, “The Role of al-ʿAql in early Islamic wisdom”. For a famous, earlier study of the hadith, see Goldziher, “Neuplatonische und gnostische Elemente im Ḥadīṯ”. For more on the concept of ʿaql in Islamic thought, see Bdaiwi, “Different Senses of ʿAql in Early Islam”.