Muslim Champions of Free Will: The Zaydi Thirty Topics Tradition in Yemen

Which Muslim theologians were among the staunchest supporters of human free will and the absolute singularity of God? One answer to this question is the Zaydi Shīʿa of Yemen, whose rich theological traditions remain largely trapped in manuscripts in Yemen and Europe.

Among the many sects and schools of Islam, the Zaydī Shīʿī tradition of northern Yemen enjoys the richest engagement with rationalist Muʿtazili theology. Mu‘tazili theologians from the early centuries of Islam were famous for championing the absolute singularity of God and insisting that God was too just to decree, will, or create evil acts, mounting a robust case for human free will as the source of evil. Most Sunni theologians rejected their Muʿtazili colleagues’ arguments, choosing instead to grant priority to divine omnipotence and insisting that humans can only perform acts in accordance with God’s decree, will, and power. After the 11th and 12th centuries, only Zaydi and Imami Shīʿī theologians continued to develop their rationalist theology upon the foundations established by the early Muʿtazili scholars.

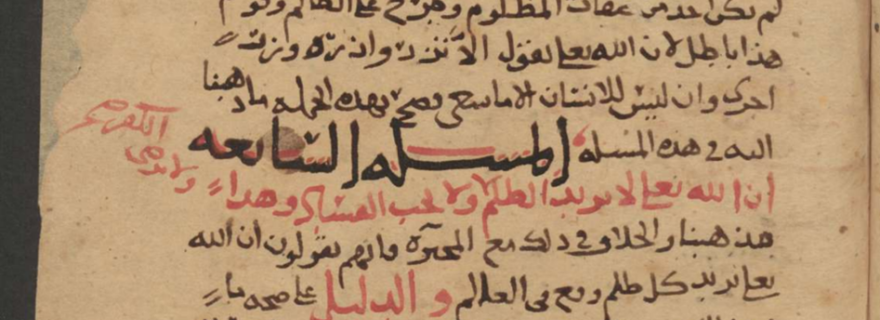

One of the most productive templates through which Zaydis expounded their rationalist theology consisted of thirty topics: ten topics on the oneness of God (tawḥīd), ten on Divine justice (ʿadl), and ten on eschatology and the Imamate. In fact, between 1150-1650 CE, Yemeni Zaydi scholars authored at least 18 texts that adhered to this thirty-topic framework, nearly all of which remain unpublished in manuscript. In a 2020 article in the Shii Studies Review, I discussed the manuscripts of these valuable texts preserved in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, Italy, on the basis of their microfilm surrogates accessible in the library of the Medieval Institute at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana (USA).

Let’s take a closer look at these thirty topics. The initial ten topics on divine oneness consist of an argument for the existence of God, six positive attributes of God, and four negative attributes of God. The positive attributes are that God is powerful, knowing, living, hearing, seeing, and eternal. The negative attributes are that God is unlike anything in His creation; God is absolutely self-sufficient; God cannot be seen by the eyes in this world or the Hereafter; and there cannot be a second divinity in addition to God.

It is among the ten topics on divine justice that we encounter some of the most complex theological issues in Islam. Zaydi scholars who follow this template, like Aḥmad b. al-Ḥasan al-Raṣṣāṣ (d. 1224), begin with a definition of “the just” as “someone who does not do anything evil (al-qabīḥ), like oppression, pointless acts, lying, and similar things; who does not forsake doing what is necessary; and whose actions—all of them—are good” (Miṣbāḥ al-ʿulūm, topic 11). Subsequent topics drive home the point that humans are entirely responsible for the existence of evil in the world and that God does not play any role in its creation:

- People’s acts—the good and the bad among them—are from themselves, not from God (Topic 12)

- God does not reward anyone save for their deeds, and does not punish anyone save for their sins (Topic 13)

- God does not decree acts of disobedience (Topic 14)

- God does not will any of His servants’ acts of disobedience, nor does He like them, nor is He pleased by them (Topic 17).

Additional topics in this section include the impossibility of God imposing obligations upon anyone that they cannot fulfill (Topic 15), affirmation of God’s responsibility and compensation for illnesses, deficiencies, and calamities (Topic 16), and argument that the Qur’an is both God’s speech and originated in time (Topics 18, 19).

The final set of ten topics is more thematically diverse. Here Zaydis address the ancient question of what to call a Muslim who commits a grave sin. The Muʿtazila famously insisted that this category of Muslim be called a “grave sinner (fāsiq),” rather than a “believer” or a “disbeliever.” Zaydis concur with this nomenclature (Topic 24) and, in contrast to Sunnis and Imami Shiʿa, argue that grave sinners will be in Hell for eternity (Topic 23) because the Prophet Muhammad’s intercession will not avail them (Topic 25). The final four topics address the leadership of the Muslim community. Zaydis affirm that the rightful successor to the Prophet Muhammad was Imam ‘Ali, followed by his sons al-Ḥasan and al-Ḥusayn, and then any of their descendants who leads an uprising and possesses exceptional degrees of knowledge, piety, liberality, courage, and administrative skills.

Even though most Zaydi works that follow the thirty topics framework remain in manuscript, curious readers should consult the published editions of Aḥmad b. al-Ḥasan al-Raṣṣāṣ’ Miṣbāḥ al-ʿulūm and al-Khulāṣa al-nāfiʿa, along with Qadi Ibn Ḥābis’ Kitāb al-Īḍāḥ sharḥ al-Miṣbāḥ, which is a commentary on al-Raṣṣāṣ’ short Miṣbāḥ al-ʿulūm. Or they may listen to a free online course in English on Miṣbāḥ al-ʿulūm I am teaching. Rationalist theology lives on in Yemen, both in Zaydi thirty topics books and beyond.

This blog entry is part of the Zaydi Studies Series commissioned and edited by Ekaterina (Kate) Pukhovaia, Leiden University.