Laylat al-Qadr as Sacred Time

Ramadan as a holy month has special rituals performed throughout its full 29-30 days, fasting from sunup to sundown, and extra communal prayers in the nights. Apart from these, it also has a special night which is specified as the pinnacle of sacred time, Laylat al-Qadr, the night of decree.

Ramadan as a holy month has special rituals performed throughout its full 29-30 days, fasting from sunup to sundown, and extra communal prayers in the nights. Apart from these, it also has a special night which is specified as the pinnacle of sacred time, Laylat al-Qadr, the night of decree. If praying in a mosque is better than praying at home, so is praying in Mecca as a sacred space even better compared to praying in a general mosque. Similarly, is praying during Laylat al-Qadr better compared to praying in the other nights of Ramadan. So, knowing the exact timing of Laylat al-Qadr becomes vital it would seem. Multiple traditions state it is on the uneven nights of Ramadan, but there are also traditions stating it is on the 19th or 21st, or on the 23rd as preferred in the Shīʿī tradition, or the 27th as preferred in the Sunnī tradition. There are even more diverse timings stated in other traditions. So, what to make of these diverse and seemingly contradictory statements?

Let’s first try to identify the meaning of Laylat al-Qadr. In chapter 97 of the Qurʾān it is described as:

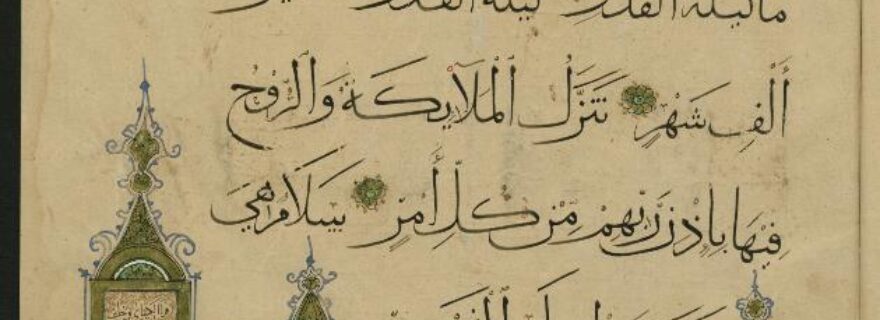

97:1 We have sent it down (anzalnāhu) in the night of power /decree /destiny(Laylat al-qadr).

97:2 And what will make you perceive/know (adrāka) what the night of power is?

97:3 The night of power is better (khayr) than a thousand months.

97:4 In it descend (tanazzalu) angels and the spirit (al-rūḥ) by leave of their Lord, with every command (min kulli amr).

97:5 Peace (salām) it is until the rise (maṭlaʿi) of dawn.

Laylat al-Qadr is therefore described here as sacred time through three aspects:

- Something supernatural is sent down in it (angels, divine command);

- It is better than a thousand months, thus being superior to normal time;

- It is the whole night, thus made accessible for normal humans.

But nowhere does the Qurʾān informs us when Laylat al-Qadr actually is. To solve this, intertextual connections were made within the Qurʾān, with prophetic narrations, and opinions of the first generations of Muslims. That the Qurʾān descended in it became the dominant position. This connection between Ramadan, Laylat al-Qadr, and the Qurʾān, is derived from the combination of a Qurʾān verse and prophetic traditions:

Q. 2:183 Ramadan is the month in which the Quran was revealed as a guide for humanity with clear proofs of guidance and the standard ˹to distinguish between right and wrong˺. So whoever is present this month, let them fast.

Tradition: “The Qurʾān descended in its totality on Laylat al-qadr, and it was between the spheres of the stars. Then God revealed it to His Messenger piece by piece.”

[Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī, al-Itqān fī ʿulūm al-Qurʾān (Beirut 1997), 1:116–7]

In this way, Laylat al-Qadr could be placed within the month of Ramadan. But the Islamic tradition encountered a problem that it rarely has: there are too many different traditions and opinions on when it is. Even though a dominant position formed that pointed to the 23rd or 27th night as the most likely for Laylat al-Qadr, all the other conflicting traditions could not be dismissed precisely because they were of the same historical authenticity. So, the uncertainty of when the sacred time exactly is was incorporated into the ritual of Ramadan. But next to embracing the mystery of the timing of Laylat al-Qadr, there is also an ingenious and unique solution to the conflicting traditions provided by the 10th century scholastic scholar Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī (d. 333/944). Instead of preferring one tradition over the other, he comes with a simple answer: They are all true! Each Ramadan, each year, Laylat al-Qadr falls on a different night, thereby over time fulfilling all the different timings mentioned in all the different traditions:

“Then we don’t have [knowledge] of [it's specific timing], and no one can point out this night. Therefore it is stated: it is a night as the night of the 27th or the 29th, except that it is established by multiple-related traditions (tawātir) from the Messenger of God in that [God] informs [us] by a sign (bi-lishāra) pointing out [the presence of Laylat al-Qadr], and so that is sought [by the believers] and [this search for it] is required in the nights [of Ramadan]. And this aspect [of searching without certainty] is taken from the related traditions in conformity [with all of them] without rejection [any of these traditions], as they are all authentic (saḥīḥ). In one year it is in some nights, in the next year another night, and in another year the last ten [days] of Ramadan, and in another year the ten middle ones, and in another year the first ten. And God knows best!”

[Al-Māturīdī, Taʾwīlāt ahl al-sunna (Beirut: DKI, 2005), 10:586–7]

Laylat al-Qadr as sacred time is elusive and mysterious. It doesn’t follow quantitative criteria, instead it is a qualitative and metaphysical concept which is connected to human intent and experience. Many Qurʾān commentators compared its hiddenness with the moment of death, each of us knows it will come, but its real moment is hidden from us. And Laylat al-Qadr is sought while we rather do not want to seek out our moment of death. Laylat al-Qadr as a name is given to us by the same text which was given on that night, marking the creation of sacred time through revelation, something that is sacred because it refers to the act of revelation itself. In Mircea Eliade’s concept of sacred time and sacred space he positions the sacred, the “transcendent,” in opposition to the profane, the “secular,” thereby linking the sacred to cosmogony, the creation of the world. Sacred spaces link creator, created cosmos, and the human daily world through ritual spaces that represent this cosmogony on earth. Sacred times point to the moment of creation, the illud tempus, and through being present and performing a determined set of acts within that timeframe the moment of creation itself is made present. Searching for Laylat al-Qadr became just as important as worshiping in it. This concept was partially based on several traditions that refer to the obligation of searching for Laylat al-Qadr, but it was also a solution constructed by the Islamic exegetical tradition itself. The pursued sacred time was, in this way, extended so that every believer with the right intention can participate in it. Because in the end, only God knows best when it is.

For a full discussion on Laylat al-Qadr, see my article “Laylat al-Qadr as Sacred Time: Sacred Cosmology in Sunni Kalām and Tafsīr” (Brill, 2017), available here: