Introducing Kawāshif al-ḥujub of al-Māzandarānī (d. 1285/1868)

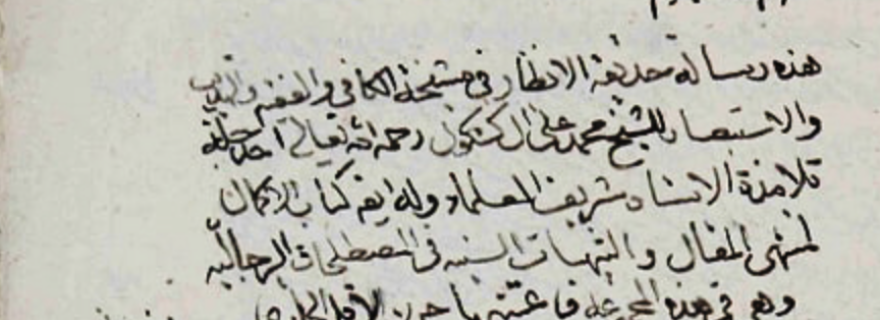

Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ al-Māzandarānī (d. 1868) was a Twelver Shiʿi jurist of the Qajar period (1789–1925 - he should be distinguished from the other Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ al-Māzandarānī, whose work was studied by Robert Gleave). His name suggests that his family came from the Mazandaran region in the north of Iran. He pursued his studies in the seminaries of Isfahan, Karbala, and Najaf. His teachers included the eminent brothers Mūsā and ʿAlī Kāshif al-Ghiṭāʾ. Having reached the highest level of juristic expertise (itjihād), Māzandarānī returned to Isfahan where he had a distinguished career. For our edition, we edited two sections from Māzandarānī’s book on jurisprudence (uṣūl al-fiqh), entitled Kawāshif al-ḥujub ʿan mushkilāt al-kutub (‘Removing the Veils from Obscurities of Books’). The Kawāshif is organised in 150 sections, each dedicated to a particular topic; the sections vary in length, some only a few lines, others running for pages. Each section comprises a ‘veil’ (ḥijāb) followed by Māzandarānī’s corresponding ‘removal’ (kashf) of it. Each veil constitutes a confusion about some matter of jurisprudence, which Māzandarānī attempts to remove, thereby unveiling the truth of the matter.

In §39, Māzandarānī examines whether non-believers can become experts in Islamic law. One of the topics often discussed in the texts of jurisprudence concerns the requirements a person must fulfil in order to be considered a legal expert (mujtahid). Some of these requirements are technical such as fluency in Arabic, familiarity with the legal verses of the Qurʾān and their interpretive traditions, and mastery of the hadith literature. Others pertain to beliefs and personal characteristics, such as religious affiliation (or lack thereof) and personal integrity. Scholars have raised questions regarding the second set of requirements. Can, for instance, a Christian or an unbeliever, become an expert in Islamic law even though, according to Muslims, a Christian has but partial knowledge of theological truths and an unbeliever none?

Māzandarānī’s text imagines an interlocutor who raises questions and issues with Māzandarānī. In this case, the issue is whether jurisprudence depends on theology. The interlocutor argues that in order to become an expert in Islamic law, one must know that there is a God; knowledge of God’s existence depends on knowing God’s attributes, among which is that He is the creator of the world and through His providence He sends inerrant prophets and imams to guide humans. The interlocutor asserts that proofs for each of these propositions regarding God and His attributes are discussed in the discipline of theology. Hence, he concludes, becoming an expert in Islamic law is dependent upon first acquiring theological knowledge.

Māzandarānī finds this argument unpersuasive. He responds that such theological beliefs are a condition of the faith of the believers in general—not of being a jurist. Hence, he argues, a person can become an expert in Islamic law even if he is a non-believer. An infidel par excellence, Māzandarānī continues, could very well be a jurist par excellence, and fully capable of deriving rulings from the principles of Islamic law using its legal sources, such that it would be incorrect to deny legal expertise of him. In Māzandarānī’s view, law is a discipline like any other. To become an expert in any discipline, one needs to master the requirements specific to it. In the case of Islamic law, one of the requirements is to acquire knowledge of Arabic, since the foundational sources of the law were revealed in that language. This knowledge can be obtained regardless of one’s religious beliefs. In his view, there is no problem if someone does not believe in a god; he can still acquire the capability of believing in the rulings of a being which, in the minds of others, is a god. Having made this argument, Māzandarānī draws a distinction between whether a non-Muslim can become a legal expert and whether the same person can serve as a source of legal authority for Muslims. In the latter role, the legal expert is also required to be a Muslim of good character. Being a legal expert is clearly different from being a legal expert whom people should respect, take notice of, and follow.